The Task Supply Problem

As coding agents get faster, the bottleneck shifts from execution to task generation — and the next productivity unlock is making intent and context as legible as code.

As agents become autonomous, the local IDE model hits a ceiling — and async remote agents become the default.

The way most developers use AI coding agents today is going to look as quaint as editing code over FTP.

Right now, the dominant model is local. You have Cursor or Claude Code or Codex running on your machine, in your IDE or terminal. You interact with it, it writes code, you iterate together. It feels natural because it’s basically pair programming with a very fast junior developer.

But this model has a ceiling, and we’ve already hit it. The local model made sense when agents needed constant steering. Early agents were like interns on their first day—you couldn’t leave them alone for five minutes. You had to watch them, correct them, keep them from wandering off into the weeds.

The local model made sense when agents needed constant steering. Early agents were like interns on their first day—you couldn’t leave them alone for five minutes.

That’s changing fast. Agents are getting autonomous enough that you can give them a task, go to lunch, and come back to a working PR. Not always—but increasingly often, and on an expanding set of tasks. Once that happens, the local model stops making sense. You’re keeping a reasonably competent worker tethered to your laptop. Close the lid and they stop. Go to sleep and they stop. Lose your wifi on the train and they stop. Why would you accept that constraint?

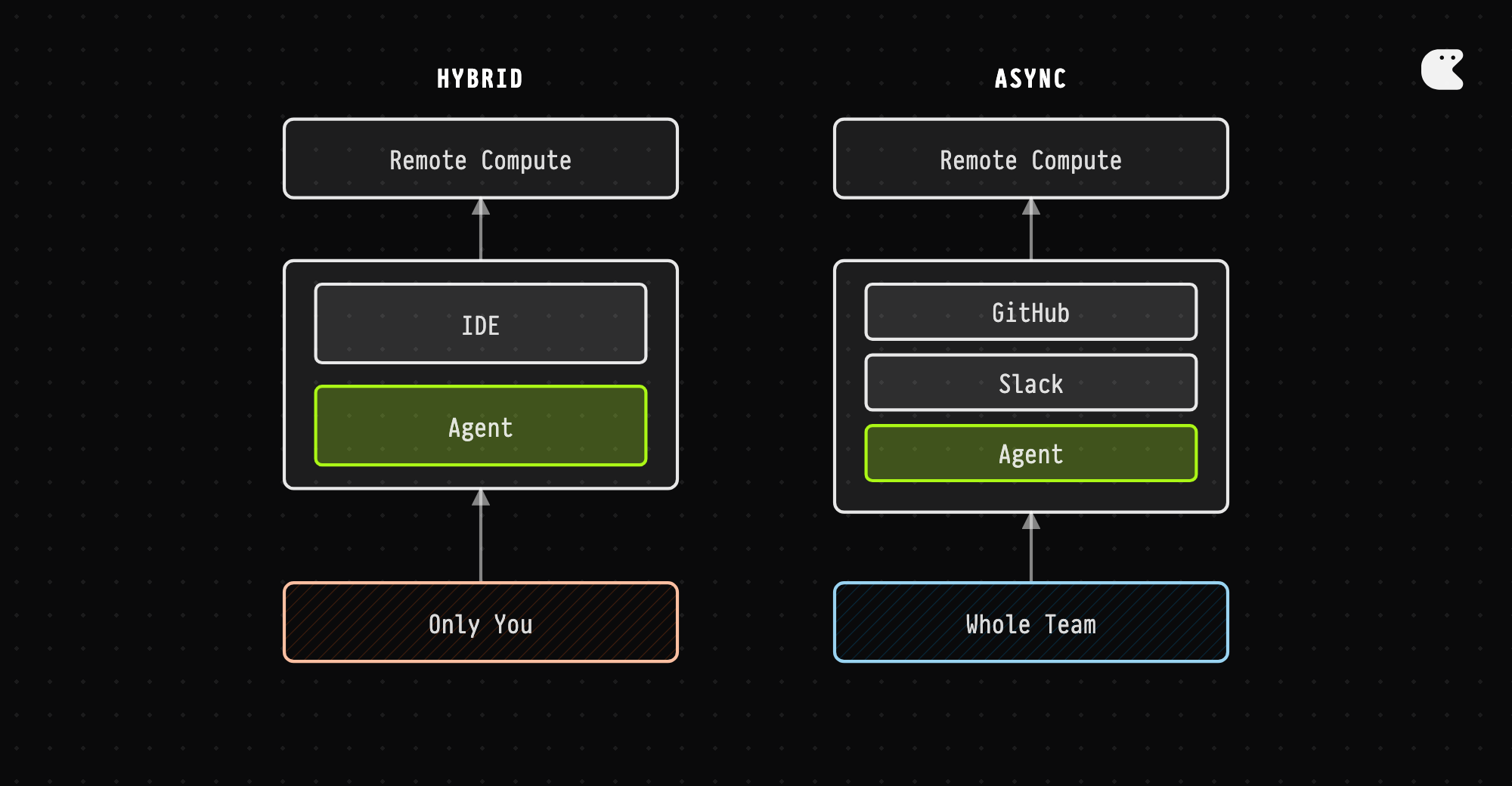

The alternative is what I’d call “async remote” agents. Instead of running in your IDE, they run on their own infrastructure. Instead of interacting with them through a terminal, you interact through the tools you already use: GitHub, Slack, Linear. You assign them an issue on Linear, they open a PR on GitHub, you review it like you’d review any other PR. The difference isn’t just where the compute runs. It’s a fundamental change in how agents fit into your workflow. Local agents are like having a coworker who only exists when you’re looking at them. Async agents are like having a remote teammate in a different timezone who keeps working after you go to bed.

Local agents are like having a coworker who only exists when you’re looking at them. Async agents are like having a remote teammate in a different timezone who keeps working after you go to bed.

There are six things that make async remote agents better, and they multiply rather than add, to the productivity of developers.

First: parallelization. When an agent runs locally, you’re limited by your attention. You might run one agent, maybe two if you’re good at context-switching. With remote agents, you can spin up ten on different tasks and let them run concurrently. You’re no longer the bottleneck.

Second: uptime. Remote agents don’t care if you close your laptop. They keep working through the night, through the weekend, through your vacation. A developer using local agents might get 8 agent-hours per day. A developer using remote agents can get 50+.

Remote agents don’t care if you close your laptop. They keep working through the night, through the weekend, through your vacation.

Third: controlled environment. Agent workloads are different from development workloads. You want specific tooling, specific models, specific memory configurations. Your laptop is optimized for running an IDE and a browser and Spotify. Agent infrastructure can be optimized for agents.

Fourth: collaboration. This one’s underrated. A local agent is tied to one developer’s machine. When Alice starts a task and goes home, Bob can’t pick it up. With remote agents, the whole team can see the agent’s work, redirect it, add context, or take over. It’s like having a shared junior developer instead of a personal one.

Fifth: platform-native interaction. Local agents have to push their work somewhere. They create a PR, post a message, update a ticket. But they’re visitors to those platforms. Remote agents live there. They see the whole context—the PR comments, the Slack threads, the Linear discussions. They’re not just pushing out; they’re ingesting the team’s actual working state in real time.

Sixth: security and sandboxing. Running arbitrary agent code on your development machine, with access to your credentials and filesystem, is a security posture that will look insane in retrospect. Remote agents can run in isolated containers with scoped permissions.

None of these individually would flip the market. Together, they create a leverage gap that widens over time.

None of these individually would flip the market. Together, they create a leverage gap that widens over time.

The obvious objection: what about tight-loop iteration? Sometimes you want to make a change, see what happens, adjust, try again—all in a few seconds. That’s where local shines. Async adds latency, which kills that workflow. This objection is correct but less powerful than it seems, for two reasons.

First, tight-loop work is a smaller fraction of total development time than most developers think. We remember the intense debugging sessions, the rapid prototyping, the flow states where we’re deeply interactive with the code. But we forget the hours of grinding through well-understood tasks: writing tests, updating dependencies, fixing routine bugs, adding features to established patterns. That work is boring precisely because it doesn’t need tight iteration.

Second, the fraction of work requiring tight iteration is shrinking. As agents get better at getting things right the first time, as they get better at generating tests that verify their own work, as they get better at explaining their changes so review is faster—the amount of human steering per unit of output drops. The tight loop becomes less necessary. This is a convergence thesis: async wins both because the delegate-able pie is bigger than we thought, and because the pie is growing.

This is a convergence thesis: async wins both because the delegate-able pie is bigger than we thought, and because the pie is growing.

There’s a more sophisticated objection: hybrid architectures. Cursor is building background agents that run remotely but interact through the IDE. Claude Code has remote execution options. The argument is that you can get the parallelization and uptime benefits while keeping the local UX.

This is the real competition to pure async agents. And it’s a reasonable bet. But I think it’s wrong, for a subtle reason. The distinction isn’t where the compute runs. It’s where the agent lives. When an agent lives in your IDE, its work is visible to you. You see the diffs, the terminal output, the intermediate steps. To share that with your team, you have to push it somewhere—commit the code, post a message, update a ticket. When an agent lives on GitHub and Slack, its work is visible to everyone by default. The team sees what it’s doing as it’s doing it. The discussion, the false starts, the corrections—they’re all in the permanent record. Anyone can jump in.

This seems like a small difference, but defaults matter enormously. History shows that default-on beats opt-in even when opt-in is available. The extra friction of “share my agent’s work” means most work stays private. The team loses visibility, which means less distributed oversight, which means more bottleneck on the original developer.

History shows that default-on beats opt-in even when opt-in is available.

There’s also the bidirectional context issue. An agent in your IDE sees what you show it. An agent on Slack sees the actual team conversation. It notices when someone says “actually, we changed the requirements” in a thread. It doesn’t need you to copy-paste that context; it was already there, listening. Some people will resist this transition. Developers have strong attachment to their personal tools, their local configurations, their sense of control. “I want to be able to tinker with it” is a common objection. This objection will not survive contact with competitive reality.

The productivity gap between async and local agents is going to be large, something like 10x. We’re already seeing this with early adopters. Ten parallel agents working around the clock versus one agent that stops when you stop is not a close contest. When your competitor is shipping features at 10x your pace, your preference for local control becomes expensive. You either adapt or become irrelevant. This is exactly what happened with GitHub Copilot. Many developers resisted it. Then they watched their colleagues ship faster. Now it’s table stakes. The developers who insist on local agents will be like the developers who insisted on Emacs when everyone moved to VS Code—technically right that their tool is more powerful in some abstract sense, but increasingly marginal to how real work gets done.

When your competitor is shipping features at 10x your pace, your preference for local control becomes expensive. You either adapt or become irrelevant.

There’s one objection I can’t dismiss: security and compliance. Remote agents mean your code, context, and credentials live on someone else’s infrastructure. For some companies—finance, defense, healthcare, paranoid enterprises—this is a hard blocker. Maybe this gets solved with better security postures (SOC2, VPCs, self-hosted options). Maybe remote agents actually become the more secure option because they’re more auditable than random code running on developer laptops. Maybe it creates a permanent carve-out where 15-20% of the market stays local for compliance reasons. I don’t know. This is genuine uncertainty, not false modesty. If I’m right, the implications ripple outward.

Here’s what these ripple effects look like:

IDEs become editors, not platforms. If agents live on GitHub and Slack, you only open your IDE for the human touch-ups—the creative work, the tight-loop exploration. The IDE vendors that see this coming will adapt. The ones that don’t will become Notepad++.

Team structure changes. If one developer can orchestrate ten agents, smaller teams can handle larger codebases. The “10x engineer” becomes the “10-agent orchestrator.” Hiring shifts from “writes code fast” to “decomposes problems well and reviews accurately.”

Junior developer roles transform. When agents handle execution, juniors either become agent supervisors—reviewing, steering, catching errors—or they focus on the irreducibly human parts: talking to customers, translating ambiguous requirements, exercising judgment in novel situations.

Platform power consolidates. GitHub, Slack, and Linear become more critical infrastructure. Agents that integrate deeply gain advantages. Switching costs rise. This is probably bad for the ecosystem but good for those platforms.

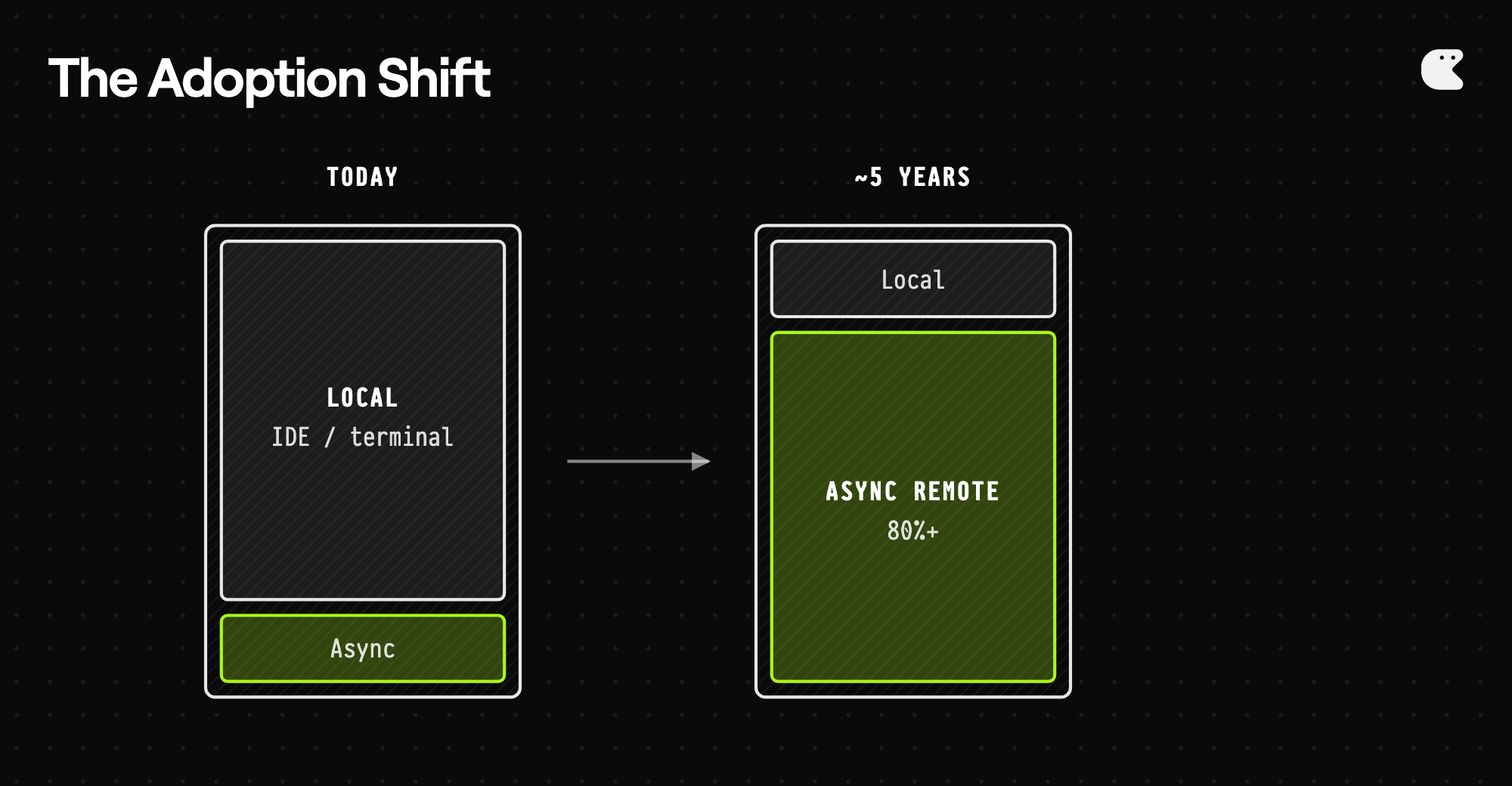

I should be clear about what I’m claiming and what I’m not. I’m not claiming that async remote agents are better for every task. They’re not. There will always be exploratory work, creative work, rapid-iteration work where local makes sense. The question is what percentage of total agent-assisted coding that represents. I’m not claiming the transition happens overnight. Workflow changes are slow even when they’re clearly better. People have to learn new habits, teams have to coordinate, tooling has to mature.

I’m claiming that async remote agents become dominant—let’s say 80%+ of agent-assisted coding—within about five years. Maybe faster if capability improvements accelerate. Maybe slower if I’m wrong about adoption friction. I’m claiming this happens not because developers choose it, but because competitive pressure forces it. The productivity gap will be too large to ignore.

I’m claiming that async remote agents become dominant—let’s say 80%+ of agent-assisted coding—within about five years.

This is, I should disclose, my bet. I’m building a company in this space. That means I could be seeing what I want to see. Pattern-matching evidence that supports the thesis, discounting what contradicts it. But I’ve tried to steelman the objections. The hybrid architecture threat is real. The tight-loop use case is real. The security concerns are real. I don’t think any of them are fatal, but reasonable people can disagree.

What I keep coming back to is the math. Ten agents working around the clock, versus one agent that stops when you stop. Parallel execution, versus serial. Default-visible to the team, versus opt-in sharing. The local model was right for where agents started. It’s not right for where they’re going. We’re about to find out who’s right.