For agents, there really are dumb questions

Agents can RTFM. Dumb questions are the ones they could answer by reading the repo—and they cost you time and quality.

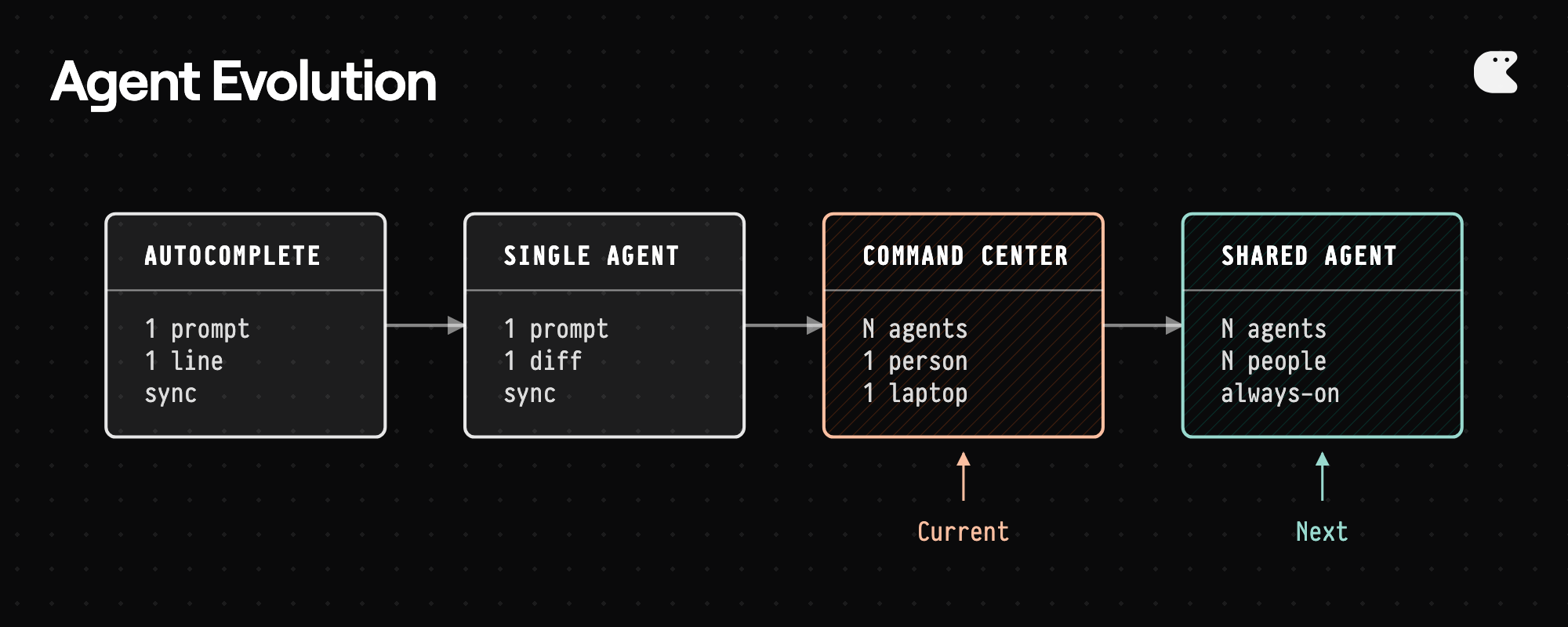

Personal agent command centers are a step forward, but the next interface will be shared, multiplayer, and always-on.

OpenAI just shipped the Codex app: a desktop command center for managing multiple coding agents in parallel. It’s a real step forward. Not because the model got smarter, but because the interface reflects a shift in thinking from “one person, one agent” to “one person orchestrating many agents.”

That’s progress. But we think there’s another step coming.

The Codex app does several things well. Agents run in isolated worktrees, so they don’t conflict with each other or your local git state. Skills let you bundle instructions and scripts for reusable workflows. Automations handle background tasks like issue triage and CI monitoring. You can supervise multiple long-running tasks without babysitting a terminal.

This is genuinely useful. It moves past the “single prompt, single diff” era into something more like delegation.

While the command center is an improvement — it’s not enough. It’s single-player by default. It belongs to one person’s account, context, and timeline. It runs on one laptop — and when it’s closed, the work stops.

The next agent interface should be multiplayer: cloud-based, always-on, and wired into the team’s knowledge and tools. It should keep working even when nobody’s laptop is open.

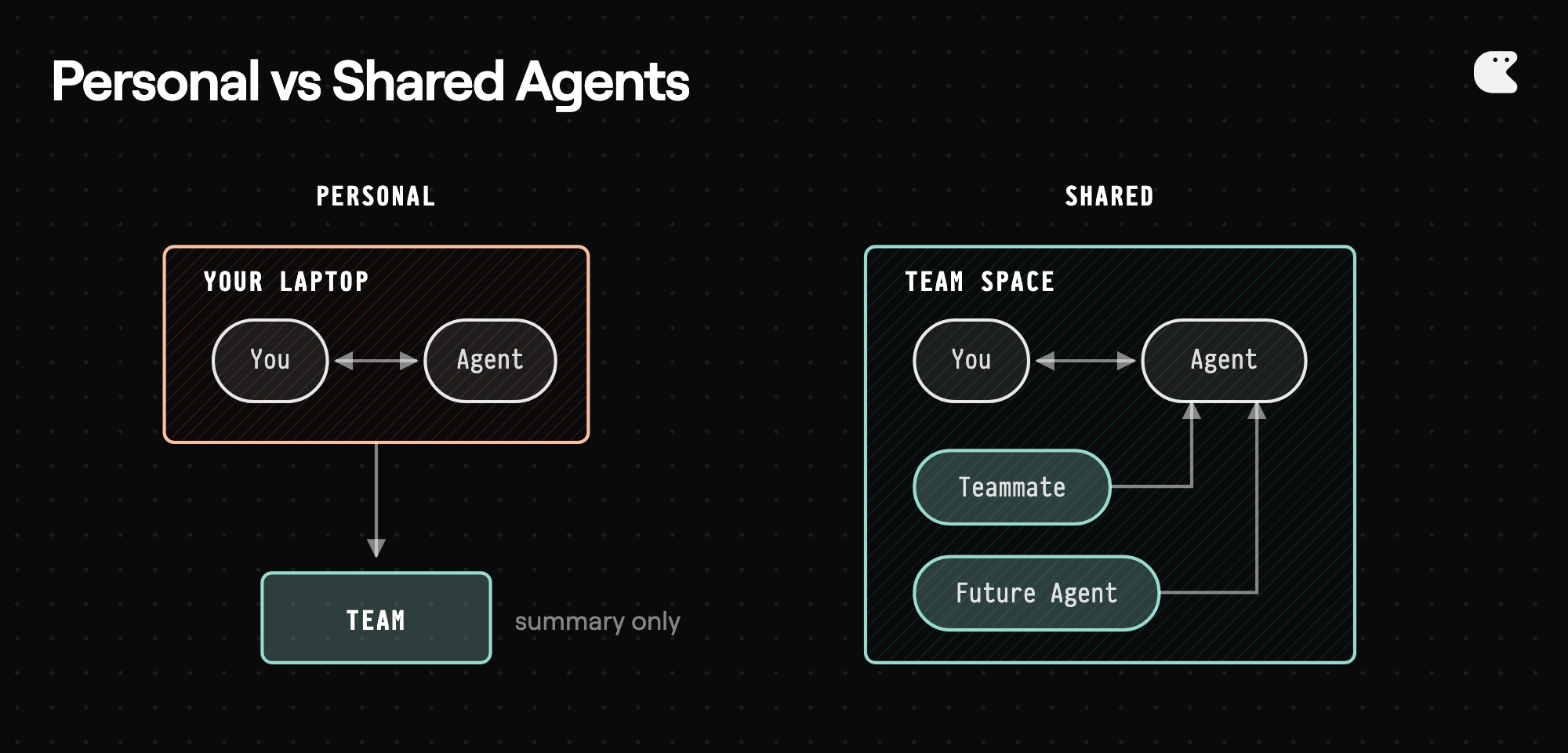

A shared agent lives where the team already works. It has its own GitHub account. It shows up in Slack and Linear. You can assign it an issue, mention it in a thread, or review its PR — the same way you’d work with a human teammate. Multiple engineers can collaborate with it together, in the same conversation, building on each other’s input.

This isn’t just a convenience. Some things are structurally different when the agent is shared.

First: multi-party collaboration. With a personal agent, the session belongs to one person. Two engineers can’t naturally work with the agent together — one drives while the other watches, or they hand off and lose context. A shared agent exists in the spaces where humans already coordinate, so collaboration is default, not an extra step.

Second: the context trail. Personal agents are getting better at memory. The Codex app can reuse skills, run automations, keep session history. That reduces personal amnesia. But it doesn’t fix organizational amnesia. When the interaction happens in a private app, the team can’t search it, link to it, or build on it. You can summarize a session, but you can’t share the real artifact: the back-and-forth, the failed attempts, the reasoning that mattered.

With a shared agent, the conversation is the artifact. It happened in a thread the whole team can see.

Here’s the part that surprised us: the primary beneficiary of a shared context trail isn’t humans.

It’s the agent. A good agent should learn how your team builds — why an architecture won, which constraints matter, what broke last time. That knowledge lives in issues, PR discussions, and chat threads. If your agent lives in private sessions, it can’t retrieve that history, because the history never enters shared infrastructure. If your agent lives in shared spaces, context compounds. That’s a flywheel personal command centers can’t spin.

The Codex app matters. It signals that the industry has moved past simple autocomplete into real delegation. But the problem is no longer “can an agent write code?” It’s “how do teams supervise, delegate to, and collaborate with agents at scale?”

A personal command center is one answer. We think the next step is making that command center shared — multiplayer by default, not single-player with integrations bolted on.

Here’s a simple test: if your agent can’t be @-mentioned and reference historical team context, it’s still a personal tool.

Personal agents won’t disappear. They’re great for private exploration and latency-sensitive work. But for teams building real software together, the interface matters more than we’ve appreciated. The difference isn’t the model. It’s where the agent lives — and who gets to work with it.